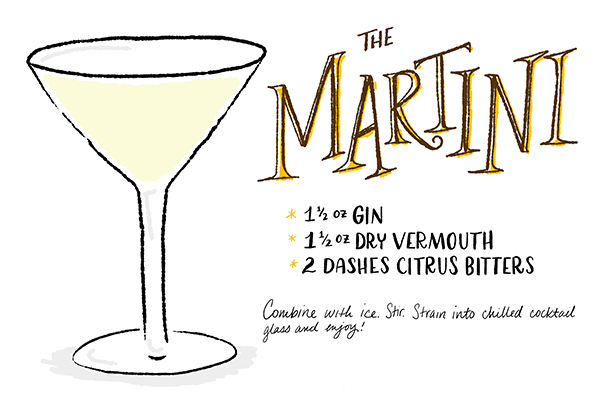

Today we’re continuing our mini back-to-basics cocktail series with perhaps the most classic of cocktails. So what makes a Martini a Martini? When it has gin and vermouth and some dashes of bitters, and is very very cold and very very delicious. Pretty simple, right? Right. – Andrew

Illustration by Shauna Lynn for Oh So Beautiful Paper

The Martini

1 1/2 oz Gin

1 1/2 oz Dry Vermouth

2 Dashes Citrus Bitters

Combine with ice. Â Stir languidly. Â Strain into a chilled cocktail glass and enjoy.

That’s about it. Gin, vermouth, bitters, ice. It’s so simple, and so perfect.

It’s also a guide, not a law. Dry gin and dry vermouth will get you, not surprisingly, a Dry Martini: sharply herbaceous and clean. Or maybe you want something with less bite: try Ransom Aged Old Tom Gin and substitute a bit of blanc vermouth for the dry, as we did in Nole’s beautiful photographs. The result is much smoother, a bit sweeter, and a lot maltier – a lot more like the Martinez, but still recognizable as a Martini. (p.s. Lately I’m a big fan of Hella Bitters’ Citrus Bitters for any version of my Martini.)

And yet lots of people feel the need to mess with this formula in unnatural. Vodka Martinis? Sour Apple Martinis? S’moretinis? The list of monstrosities goes on. None of these deserve the title “Martini.”

So: a Martini is a Martini when it has gin and vermouth and bitters, nothing more and nothing less. Throw in something else – vodka in place of the gin – or take something out, like the vermouth – and you have another drink entirely. Drink and enjoy it if you like, but it’s not really a Martini.

That’s one of the best and worst things about cocktails: the names. It’s a convention and conceit among bartenders and mixologists that every unique combination of spirits and mixers deserves its own name. A little self important and a little fun, in even measures. So even though the Sidecar and the White Lady and the Margarita and the Daiquiri are all simple variations on a theme, the Sour, they’re all unique drinks and they all get their own names. Since there’s an infinity of possible recipe combinations, a new drink with a new name is always within your reach, even if it’s just a dash of this and a splash of that away from someone else’s recipe.

(At least, I don’t think every single possible drink combination has already been tried by someone. But I suppose it’s possible that it’s all been done before. People really like their booze.)

And in that world of infinite combinations, and infinite possible names, a relative handful of named drinks have stood the test of time. The Manhattan. The Sazerac. The French 75. And the Martini. They survived when so many other recipes and their fleeting names were forgotten because they’re good. They have standard(ish) recipes and enduring names because they’ve earned them.

I said the names were one of the best parts of cocktails, but they’re also among the worst. With those names, and the handy guidelines that roughly define them, come the scolds and the pedants and the rule enforcers. Virtually any discussion of drinks and cocktails will eventually attract some of these folks who will leap at the chance to tell you how you’re doing it all wrong and you must Follow The Rules and make your drink exactly this way Or Else.

If our Friday Happy Hour posts have a thesis, it’s this: there’s a better way in between the Appletini and the scold. That we can move beyond the immaturity of modern American drinking by learning from the great recipes of the past, without turning into nitpickers who obsess over the rules. Drink well, the way you like.

Oh, and something something moderation.

Photo Credits: Nole Garey for Oh So Beautiful Paper